Earlier this week, I gave a jobs talk at a small panel at Emory University’s Law School, on behalf of their International Law Society.

It was a great opportunity to think through how a law background is most useful for the international development sector.

The panel was organized around a set of questions to dig deep into what it’s like working at the United Nations, in an NGO, and in global development.

Here’s what I said framed around the key questions. I’ll follow that up with a few notes I wish I had more time to get to, and a few other thoughts.

Tell us about your background.

First off in this context at Emory Law School, I had to open by stressing: I’m not a lawyer. But I’ve worked around some specific human rights and rule of law challenges in a career spanning 15 years.

In terms of background, I studied philosophy, politics and economics in undergrad. And then economics and statistics in grad school.

I’ve since worked in about 20 countries, with 3 UN agencies, 1 BINGO (big international NGO), and split my time roughly in half between HQ and field positions.

When did you know you wanted to work in international field: how did you get into the field and why do you stay?

My family is from Ecuador, and I grew up between the US and Ecuador. This probably gave me a fair amount of cognitive dissonance, implicitly comparing how systems worked between the two countries. So there was always a bit of a concern with social justice questions stemming from my upbringing.

How I got into the UN is a story of luck, but with a strong moral to it.

When I graduated from college, I worked two jobs: one at a legal think-tank run by a retired Columbia law professor, the other at a mental health research project in Brooklyn. One day I got a call from a lady at the UN who wanted to see if I were interested in coming in to interview for a position.

Absolutely.

I went in with my suit and tie, did the interview, and a written test. I had read everything I could about the unit, all their online reports, the bios of team members, just… everything. I was honest in the interview, and managed to find some mistakes in the written test itself.

A few days later, I was offered the job.

Turns out, my new boss had previously worked at a research firm where I had submitted an application to before graduating from college. I never heard back from them, but she had gone to them for any interesting CVs, and they shared mine with her.

I was extraordinarily lucky.

But beyond your never knowing how your big chance can come up, I think one major moral of my story is: Don’t listen to those who keep pushing ‘networking networking networking’ as the only answer into competitive jobs. Rather, keep trying, learn from what works and what doesn’t, and then prepare like hell when your chance comes up.

And when did I decide to stay in international development?

After finishing my graduate degree, I did an interview at Goldman Sachs. It was a neat position applying political risk models to improve the credit ratings of national economies like Mexico. At the interview I was asked what I thought of international capital controls. I reacted with, “Well, they’re very bad for the poor.”

Yeah, that wasn’t the right answer.

It was about then that my values and devotion to working on social problems crystallized. I focused on trying to gain international experience, as my work had been in New York until then. And I got jobs in Thailand, Afghanistan and Sudan for the next few years after that.

What has helped you get to where you are, and what advice would you have for the students who want to set off in a similar direction?

When I originally thought of my response to this question, I came up with: persistence. You can’t give up or easily be rattled.

But I don’t think persistence covers it. It’s more like ‘adaptability.’

A willingness to adapt has been critical. To be able to learn new things, new materials and ideas, and to learn from your successes as much as failures.

For instance, one assignment I had was to help build National Action Plans to implement UN Security Council resolution 1325 (2000) on women, peace and security. This resolution looks to address things like sexual violence in conflict, and protect women’s and girls’ rights in situations of conflict. I worked in three countries, with representatives from their national governments, civil society organizations, academics, and so on, to help build these National Action Plans, including designing activities and the tools to monitor their implementation.

No one was about to train me to do this work: they wouldn’t have had the time if they wanted to. It was something I had to learn on my own, I:

- Spoke with colleagues.

- Read a ton of books, reports and papers about these countries, and the issue area.

- Tried and tested the material across the three workshops.

So this leads me to another piece of advice: you have to have a fair amount of creativity and an entrepreneurial spirit to go neck-high in international development work. You have to work with colleagues, with clients or the communities you’re supporting. Get everyone together in a room to agree on language, to identify the root causes of a challenge, and figure out responses together. It’s a lot about adding value to others, and thinking through what people need – from their perspective.

A final point of advice: Know when to walk away. Not every job is for you, not every experience is either. Learn what you can from them, but know when to walk away and find something more suited to you. I’ve been in positions where I learned all there was to the work in three months or less. My skills were atrophying by not being used effectively for the organization. Or I just got bored. These things happen.

So I kept on looking. I did take chances because of this, in going to places like Afghanistan which aren’t always fun. But it gave me a continuous learning curve by being willing to walk away, before I got too comfortable.

What is the most rewarding part of your job?

It was around now that time started running out, so we clipped our answers a bit more.

Working on complex social problems. Getting the chance to learn about a new country, and getting to the root of a particular challenge. What does that look like? It’s about getting the right analysis on the page, understanding it through the perspective of those impacted.

What skills are you looking to hire?

Some things are presumed: if you’re coming from a place like Emory, or Harvard or Columbia — you are smart, have ambition and strong analytical skills, and are knowledgeable in your expertise area. It’s difficult to differentiate among these from the get-go.

But one of my biggest challenges these days is working with experts to apply their knowledge.

I’ve hired recently a range of academics, who may be among the best in the world in terms of their expertise, knowing the latest literature and being really interesting on their issue area. But I’ve had a hard time making use of their work, without rewriting it myself or looking into how to apply their expertise.

So being able to use the expertise and knowledge to solve the challenge at hand is a really specific skill I’m increasingly looking for. A willingness to be open and problem-solve.

How do you see this field changing in the future? What do you see the coming trends in this field that we should know about?

Three evolving patterns come to mind.

- Follow the money. Yes, you have to have passion and an interest in international development — let those guide you. But follow the money. Always ask, where are the resources going to in international development? What are the emerging priorities getting funding? Knowing this will help you know what opportunities exist, and to be able to get ready for them.

- Erosion of the North-South divide. It used to be, not even 15 or 20 years ago, when I started, that it took the right degrees from elite universities to get started running a program in the developing world. But things are changing. Skills in the Global South are growing, and the reality is, we will never know a country or locale society in the same someone from there does. For instance, I’m really focused on building partnerships with local actors right now. I can bring a team of experts, data analysts and so on, which can do really great work, and probably better analytical work than the on the ground in somewhere like Liberia. But a Liberian will know their country in a way I never could. So we’re trying to find ways to build partnerships to leverage the advantages we each bring to the table.

- Better framings of the problem are always needed. In global development, we’ve gone through cycles of thinking the problem is economic growth in the developing world. We went on to think of human development or human capabilities as the real focus. Lately, we’ve been focusing a lot on randomized control trials being able to tell us what works and what doesn’t. People argue that institutions matter. And complexity theory and systems approaches are being used.

Working to develop better, more accurate framing of the challenges of global development is an open area that will new thinking. That’s because, if we can better understand the problems – we can better deliver responses.

***

So those were my responses to the main questions we were able to get to during the panel.

Then started the Q&A from the students…

We ran out of time, as these things usually do, so just a couple of questions got through.

How does one apply expertise?

You focus on your client. On understanding their worldview, what motivates them, and what their interests are. Aim to understand what their perspective is, what you offer, and then shape what you bring to them in their own terms.

How big a player is the World Bank in development?

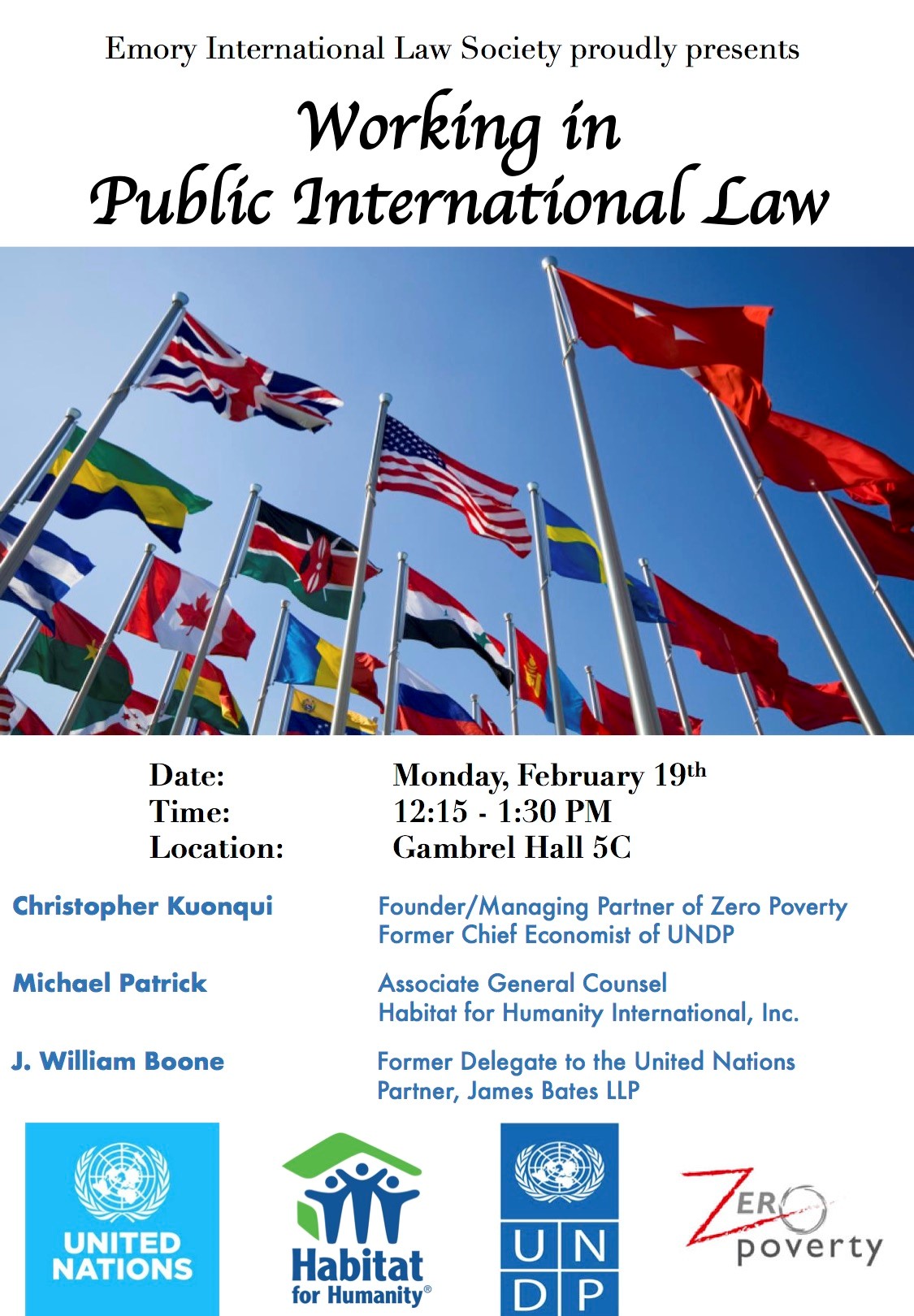

They’re the big boys on the block. I had shared some slides on funding opportunities, and here is where the World Bank sits:

WB is the dark blue.

This makes them really important. They also tend to have the most funding and resources to support staff. Better training programs, and so on. The state of intellectual debate is generally of a higher caliber.

Now, they’re not the only place, and I’m not saying they’re the best place, but they certainly are big players in the sector.

***

…and then we moved on to the one-on-ones

I have to say up-front, there were some great questions.

Q: I’m from East Asia, and I’ve worked in Australia, Hong Kong and a few other places. How can I leverage my international experience for a job in international development?

Q: I’m from East Asia, and I’ve worked in Australia, Hong Kong and a few other places. How can I leverage my international experience for a job in international development?

Find what employers are looking for. And try to connect that to an experience you’ve had. Depending on what you did in these different work experiences, there is a portable skill or approach you’ve taken to working with clients that can add value to the hiring organization. Write your CV in a way that helps connect those dots for a potential employer.

And then learn and iterate on your CV from there. See what works, what doesn’t get a response, and keep improving your applications.

Q: Do you know of any coaches or people who can help recruit into the field?

You know, I’ve never met anyone who has used a coach, at least that I’ve known of. But for sure, there are resources out there to learn more about the field, and find opportunities.

My top suggestions are: Devex.com, and unjobs.org. You’ll find a big careers section and database in Devex, and UN Jobs is a wonderful place that aggregates jobs from a bunch of UN and NGO opportunities.

Edit after the fact: As the line built-up in the one-on-one discussions, I regret not directly mentioning to this student: go to this blog! If you’re reading this, dear student, please write me, you have my card.

See — adaptability? Really important. Don’t think I’ll miss that chance again.

Q: What’s the situation really like in Afghanistan? Is it as rosy as we hear in the news?

First off: I’m not sure about the premise here. The news is typically filled with bad news from Afghanistan these days.

Now, there is progress, that’s for sure. Girls’ education has skyrocketed compared to pre-2001. Health indicators are going up, absolutely.

A law student from Afghanistan also entered in the conversation at this point, and we went on to discuss the situation since President Ashraf Ghani came into power. Ghani is a Columbia anthropology PhD, taught at Johns Hopkins, and then worked at the World Bank for a long time. He wrote the book on ‘fixing failed states’ (Fixing Failed States: A Framework for Rebuilding a Fractured World).

This prompted an interesting question:

Q: Is there a backlash against being neocolonial?

There sure is. Gone are the days when, equipped with the right degree and desire, you can walk into the developing world, get a job, and run a program delivering aid. The challenges are much more nuanced. How do we leverage what we each can bring to the table, do some good, and bring value to communities, governments, and marginalized groups? It’s a lot about managing the erosion of the Global North/South divide: which is the way things should always have been.

Oxfam, for instance, moved not even a year ago, its global HQ from London to Nairobi in the direct effort to get closer to the communities Oxfam servces. This is recognition of the need to decentralize power, and expertise and development know-how is its own form of power.

The situation is changing. How we provide new responses, new relationships grounded in authentic partnership, and new impact is a question for us to work on together.

Q: How can we bring together international law, medicine and improving the healthcare system in places like Egypt?

This one stumped me. The law student was from Egypt, had completed his medical school training, was doing law now, and next year was onto his master’s in public health.

We went over a number of points but three things stuck with me (aside from wanting to see what mark this extraordinarily over-educated person will leave on this world).

First: We got into how funding works with global development. And generally my response was, it’s very top-down. An organization, say like the Gates Foundation, will review WHO reports, do their own data analysis, and study the issues, then draft up a strategy on what they’d like to do based on the evidence and their own internal interests. From there, they’ll issue a call for proposals, to which different companies, firms, NGOs, international organizations, and so on, can bid to get the funding and implement the work.

Cue the follow-up question:

Q: How do you influence what donors do?

That’s challenging as an individual, but one example that comes to mind is the life and career of Jeff Sachs. Take a look into a useful book on his impact, by Nina Munk. (I’ve listed the book in a references section below.)

We went on for a bit discussing Sachs’s remarkably impressive bio (Harvard PhD, tenured at 28), and how he got involved in development work. One of Sachs’s central ideas was to funnel resources into the creation of the Global Fund to Fight Aids, Tuberculosis and Malaria, which went on to be behind much of the recent progress against these health challenges in the last 15 years or thereabouts.

So this was the second thing that stuck with me: you may need to be a person of Sachsian scale to individually change what donors fund. All meaning, needing to work with others and the soft skills that requires, is really essential.

Q: How do we improve the healthcare system as a whole in the developing world? Not only public health institutions, but private hospitals, which is where the wealthy turn to in places like Egypt.

Of course, I’m not a super specialist on these issues – so if you’ve some further insight into this, please do remark in the comments below, or send me an email.

But here’s the third thing that stuck with me from this conversation: I’ve not heard before anyone question the whole-of-healthcare system in my discussions on public health. The focus of work that I’ve been around (like the Global Strategy on Women’s, Girls’ and Adolescents’ Health) is overwhelmingly on improving the public health system. So, while I’m sure people are thinking on this, it was a fresh perspective for me.

***

Resources mentioned:

- www.devex.com

- www.unjobs.org

- Ashraf Ghani and Clare Lockhart, 2009, Fixing Failed States: A Framework for Rebuilding a Fractured World

- Nina Munk, 2014, The Idealist: Jeffrey Sachs and the Quest to End Poverty

.

What’s your experience in law and development careers? What would you like to hear more about? Leave a comment or question below.

One reply on “Jobs talk: Emory Law School – Working in Public International Law & Development”

Very usefull,

Thanks Chris!